LEARNING IN Activism | Building alliances

Migrants for Aboriginal Rights

By the middle of the twentieth century, migrants from many countries had been encouraged to come to live in Australia, to build up the population and provide labour for the expanding economy. But when they arrived, they often found that Australia was far from welcoming. In fact, many migrants, including those from southern Italy, were met with hostility and abuse. Facing these difficult conditions themselves, it was then an uncomfortable lesson to recognise that they had played a role in reinforcing the colonial hold over Aboriginal people’s land.

Some migrant community organisations refused to accept this position, instead trying to transform their new country into one where justice as available for everyone. It was not easy approaching Aboriginal people to ask advice about how best to support the Aboriginal cause. Frank Panucci, from FILEF and the Australia Council, had been introduced to Kevin Cook through union activists like Serge Zorino and Hal Alexander. He talked in 2002 about his experiences as a member of FILEF as it built up this relationship:

Those first meetings were more about us learning what Indigenous issues were about in Australia and cutting through a lot of the mythology about it. Mythology both in the sense of public representation but also the mythology of left-wing views, because that’s where our background was.

We went through a pretty steep learning curve.

We learned that there were similarities between the issues but they were at a tangent. As migrants, we went through experiences which had the same label in certain aspects in our lives, experiences of racism and structural discrimination. But the fundamental issues were different. The issues about the rights of Indigenous people, of being people who suffered colonisation, that had nothing to do with our experience of how we moved into this country and participated in it, and the way that the forces that control this country, then and still now, reacted to migrants and Indigenous people.

There were similarities between the migrant experience and the Indigenous experience, which were related to issues of racism …. But it became pretty clear to most of us, that the fundamental rights issues were about ownership of land. Aboriginal people, as dispossessed owners of the lands of this country, can turn around and say, ‘Well it’s easy for you ‘cause you can pack your bags and go, but this is my country!’

I suppose that it’s that kind of stuff that actually changed for me and I think for an organisation like FILEF, because it placed a whole issue of indigenous rights into the broader social struggle within Australia. So, from those mid 1980s, we incorporated it into our actions, into the way that we saw Australia. We came to see that unless you addressed indigenous issues, you would never actually achieve the transformation of this country that we wanted.

We had to learn that you can’t fall into the trap of thinking you know the answer about what Indigenous people should and should not do. In a way, this transcended Indigenous issues for us, because it actually transformed the way that we dealt with community generally. The important thing is how you transform yourself and become a spokesperson OF and not a spokesperson FOR.

We found we had an ongoing reference point in Kevin and Tranby. Whenever we felt the need to talk about something, we knew we could pick up a phone and the advice we would get, the counsel we would get, would be a measured counsel which would not be an imposition on us.

Another activist has described the uncomfortable process of seeking out Aboriginal advice. Sonja Sedmak is a playwright who was involved in the crafting of the script for the 1986 play ‘Leave us in Peace’, performed by the FILEF theatre group for the UN International Year of Peace. The company wanted to ensure that their play recognised Aboriginal people’s demands for recognition, but as Sonja explained, they were unsure of how they would be welcomed. They felt naïve, worrying that they would appear patronising to Aboriginal people as they tried to work out the most appropriate way to offer support. These exploratory and sometimes clumsy networks nevertheless strengthened over time in shared campaigns to end uranium mining on Aboriginal land and to close down US bases in Australia and the region.

Cover of March 1987 Nuovo Paese, featuring Aboriginal women

Interview with Karen Flick in Nuovo Paese, March 1987, about land and Aboriginal women, pp 2-3. View full article

Frank Panucci explained the way that Tranby gave Kevin Cook the means to bring people together across very different networks but who shared common interests:

Kevin Cook sort of web-spun. He spun out to a whole lot range of smaller webs out there. I remember one famous barbecue organised at Tranby for a lot of us to actually meet members of the National Coalition (of Aboriginal Organisations), because obviously they were from all over the place, I think it was the first time I met Marcia. And there was this interaction there which was bought by a common interest in Indigenous stuff.

And we made our own networks, of like-minded people across the place. But still people today that I make phone calls to about different issues, and our paths cross because of work and stuff - it’d amaze you how quite often, one of the constant reference points is a certain Kevin Cook. Tranby in general, Cookie in particular.

There were common interests which brought people from FILEF into contact with Tranby as well. The Sydney sections of the Anti-Bases Coalition and the Close Pine Gap campaign met at Tranby which offered a welcoming interest in the Peace movement. In its early years with Alf Clint, Tranby had been an organisation which was sympathetic to the Peace movement. Alf had been on the Peace Council and had shared with others a deep commitment to the anti-nuclear movement. Kevin Cook had expanded this interest, with his active connections through the Federation of Land Councils to the Kokatha people at Roxby Downs in South Australia and the Yolngu in the Northern Territory, both of whom were opposing the mining of Uranium on their land. To this was added the opposition to foreign military bases on Australian soil, in which attention had been focussed on the secretive communications base Pine Gap outside Alice Springs. FILEF members participated actively in both these movements and Frank Panucci was Treasurer of the Anti-Bases committee meeting at Tranby. It was at these meetings at Tranby that Vera Zaccari met Kevin Cook and Judy Chester, opening up the communication which led Kevin Cook to intervene in the Leichhardt Council proposals to set up Advisory Committees. (see Learning in the Community)

Over the mid-1980s, Australian governments were planning to mark the 200th Anniversary of Australia in Sydney on 26 January 1988. Fifty years earlier, the Sesqui-Centenary – the 150th Anniversary – had been a ‘reenactment’ of the First Fleet landing which depicted Aboriginal people as violent but cowardly, and presented the British as benign and noble. There were widespread criticisms in the aftermath of this distorted depiction and the authorities the 1980s were trying not to repeat this sadly Eurocentric performance.

So immigrant communities had mixed feeling about the planned Bicentennial. Although Australian governments claimed they saw it as a celebration of a modern and multicultural Australian nation, official plans were still depicting its origin in a supposedly benign British colonisation. These official celebrations did not seem to recognise either the pain and damage caused to the original Aboriginal land owners or the challenges faced by the many culturally-diverse people who had come into Australia since World War 2. Yet for immigrants, just as there had been for Aboriginal people who enlisted to fight in World War 1, there were desires to belong and to be recognised as belonging. The Bicentennial seemed to offer a chance to do that – to be seen to be taking part in the nation’s celebration and to be recognised through that AS part of the nation.

Initially, artists from the Italian-Australian and other communities hoped to build on government funding to demonstrate the place of recent immigrants in the nation. An artist involved with FILEF applied for funding from a number of bodies for a project which would profile the rich cultures of working-class Turkish, Greek and Italian communities in three Australian cities – Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. The project gained funding support from the Australian Bicentennial Authority (ABA). This was initially welcomed but there was rising concern within FILEF about the narrow type of ‘nation’ that was going to be represented by the ABA celebrations. By early 1987, after a hard debate, FILEF took the difficult decision to return the money to the ABA, a major sacrifice for a small and ill-funded organisation.

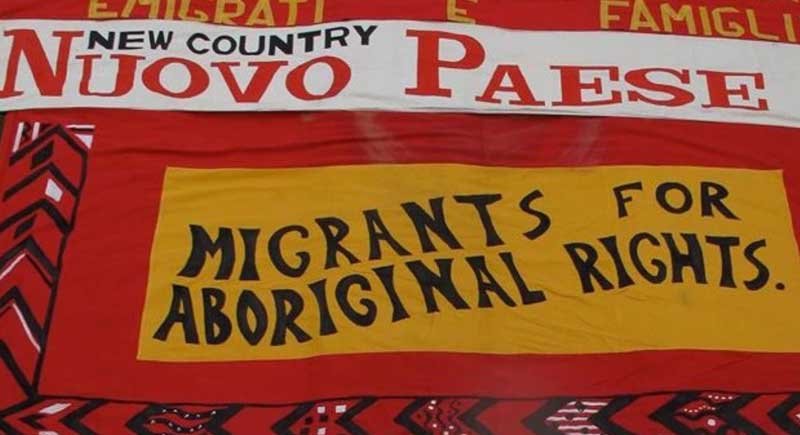

There was much press interest and public debate about the decision, and it became clear that there were other community groups along with FILEF who were unhappy with the approach being taken by official Bicentenary authorities. They came together in a new body: Migrants for Aboriginal Rights, which was in touch with Aboriginal communities through Tranby and the National Coalition of Aboriginal Organisations. Migrants for Aboriginal Rights was able to publicise the Aboriginal plans to protest against the Bicentennial across many immigrant communities. One example is the FILEF newspaper, Nuovo Paese. The December 1987 issue carried a call to readers to protest at the Bicentennial: “Demonstrate – Don’t Celebrate 88”, with a long article in Italian outlining the colonial history of British Australia and the dispossession of the Aboriginal owners.

‘Demonstrate - don’t celebrate 88!’, graphic, December 1987, Nuovo Paese

No need to read Italian – the pictures in this article tell the story!

As a result of the campaigning by Migrants for Aboriginal Rights, the members of twenty different immigrant communities – including the Greek, Chilean, Turkish and many others– came together to hold a fund-raising Solidarity Concert in January 1988. There were performers from many cultures: Bella Ciao, the Italian choir from FILEF, Solidariedad, the Philippines musicians along with Chileans, Turkish, Palestinan performers and many others. They invited Aboriginal campaigners to be the audience, to hear from these Australians of so many different backgrounds that they refused to celebrate the dispossession of the invasion. Gary Foley gave a speech at the Solidarity Concert, reported in English in the February issue of Nuovo Paese, which also carried an article in Italian about the concert and the Bicentennial protest march.

Cover, Nuovo Paese, February 1988, showing Gary Foley with the Migrants for Aboriginal Rights banner, later to be carried at the protest march on 26th January

Gary Foley’s speech from the Solidarity Concert, reprinted in Nuovo Paese, February 1988, pp 3-4, with a photograph of a member of the Filippino group, Solidariedad

So there were many people marching under the banner of Migrants for Aboriginal Rights in the protest march which took place on January 26th. Yet here too there were lessons to be learned, as Frank Panucci explained:

The organisers of the march said: ‘This march is going to be led by Indigenous people, anyone’s not Indigenous starts when the Indigenous people stop!’

And if it had been another time and we hadn’t gone through what we’d gone through – that journey in terms of learning stuff – I think a lot of people would have said, ‘It doesn’t make sense, aren’t we all in this together?’

I think that’s been the hardest thing for all of us to understand. But at the end of the day, no matter how supportive we are of the issues and how close our hearts are to that issue, it’s always been an issue about power, and I can’t undermine that building of their power. That’s the important lesson that I think we all took away from that, and still carry with us today.

The Migrants for Aboriginal Rights Bicentennial banner. Courtesy Claudio Marcello

Still from 1986 FILEF Theatre Company play, Leave us in Peace

The many people involved in Migrants for Aboriginal Rights continued to be active after the Bicentennial… The organisation succeeded in widening the knowledge among the many communities in multicultural Australia about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander demands and goals. As a result, a number of Italian-Australians became involved with Aboriginal people in political and creative work, particularly around Boomali, the Aboriginal Artists collective (located in Surry Hills and then in Leichhardt) and with connections with the Venice Biennale. So there has been lots more to this story of webs and networks!